Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) has been a major global health challenge since the 1980s, affecting millions of lives worldwide. Left untreated, HIV gradually weakens the immune system, leading to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), a condition that leaves the body vulnerable to infections and certain cancers. However, advancements in medicine have paved the way for effective HIV management, primarily through the use of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART). Antiretrovirals have transformed HIV from a fatal diagnosis to a manageable chronic condition, significantly improving quality of life and life expectancy for those living with the virus. This blog explores the role of antiretrovirals in HIV treatment, their types, mechanisms, and their profound impact on public health.

1. The Basics of HIV and Antiretrovirals

HIV attacks and destroys CD4 cells, a type of white blood cell that performs a crucial role in immune function. As CD4 counts drop, the immune system weakens, making it tough for the body to combat infections and diseases. Without treatment, HIV progresses to AIDS, often leading to deadly complications.

Antiretrovirals (ARVs) are drugs designed to combat HIV by inhibiting its capacity to replicate in the body. Since HIV is a retrovirus, it relies on a technique known as reverse transcription to reproduce. ARVs target different stages of this replication technique, lowering the viral load (the amount of HIV in the blood) to undetectable levels. Achieving an undetectable viral load is important for preventing disease progression, enhancing immune function, and preventing transmission to others.

2. The Evolution of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART)

The history of HIV treatment is a journey of medical innovation and global advocacy. Early HIV treatments had been limited and often toxic, with considerable side effects. However, the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in the mid-Nineties marked a turning point in HIV care. By combining multiple ARVs from different classes, cART effectively suppressed HIV replication, lowering viral load to undetectable levels in most sufferers and significantly improving health outcomes.

Today, ART typically involves a combination of 3 or more ARVs, selected based on their effectiveness and capacity to reduce facet effects. Modern ART regimens are often taken as single pills containing multiple capsules, making treatment extra convenient and easier to adhere to. Adherence to ART is important, as missing doses can cause drug resistance and remedy failure.

3. Types of Antiretroviral Drugs and Their Mechanisms of Action

ARVs may be categorized into numerous classes based on their mechanisms of action. Each class targets a specific stage in the HIV life cycle, preventing the virus from replicating and spreading. Here`s a more in-depth look at the main styles of ARVs:

a. Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs)

NRTIs, also recognised as “nukes,” work by mimicking the building blocks of viral DNA. When HIV tries to replicate, it incorporates NRTIs into its DNA chain, causing premature termination. This class includes drugs like zidovudine, lamivudine, and tenofovir. NRTIs were among the first ARVs developed and remain an important part of modern ART regimens.

b. Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs)

NNRTIs, or “non-nukes,” bind directly to the reverse transcriptase enzyme, blocking its function. This prevents HIV from converting its RNA into DNA, a crucial step in viral replication. Examples include efavirenz, nevirapine, and etravirine. NNRTIs are regularly used in combination with other ARVs for enhanced efficacy.

c. Protease Inhibitors (PIs)

Protease inhibitors block the protease enzyme, which HIV needs to cleave its proteins into functional units. By inhibiting protease, PIs prevent the virus from producing mature, infectious particles. PIs like lopinavir, atazanavir, and darunavir are highly effective but may require careful dosing because of potential drug interactions.

D. Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTIs)

INSTIs inhibit integrase, an enzyme that allows HIV to insert its DNA into the host cell`s genome. By blocking this integration step, INSTIs stop HIV from hijacking the cell`s machinery to produce more viruses. This class consists of drugs like dolutegravir, raltegravir, and bictegravir, which can be now commonly used because of their effectiveness and low toxicity.

e. Entry and Fusion Inhibitors

These pills prevent HIV from getting into human cells by targeting the proteins involved in viral entry and fusion. For example, maraviroc blocks the CCR5 receptor on CD4 cells, while enfuvirtide prevents the fusion of the virus with the cell membrane. Although less commonly used, entry and fusion inhibitors are valuable options for patients with multidrug-resistant HIV.

4. Antiretroviral Therapy and the Goal of Undetectable = Untransmittable (U=U)

The U=U concept, which stands for “Undetectable = Untransmittable,” is a breakthrough in HIV prevention. Research has shown that individuals with an undetectable viral load can not transmit HIV to others thru sexual contact. This has great implications for decreasing HIV transmission, stigma, and discrimination. Achieving U=U requires strict adherence to ART, which keeps the viral load at undetectable levels and enables people with HIV to live healthy, normal lives with out fear of transmitting the virus.

5. Side Effects and Challenges in ART

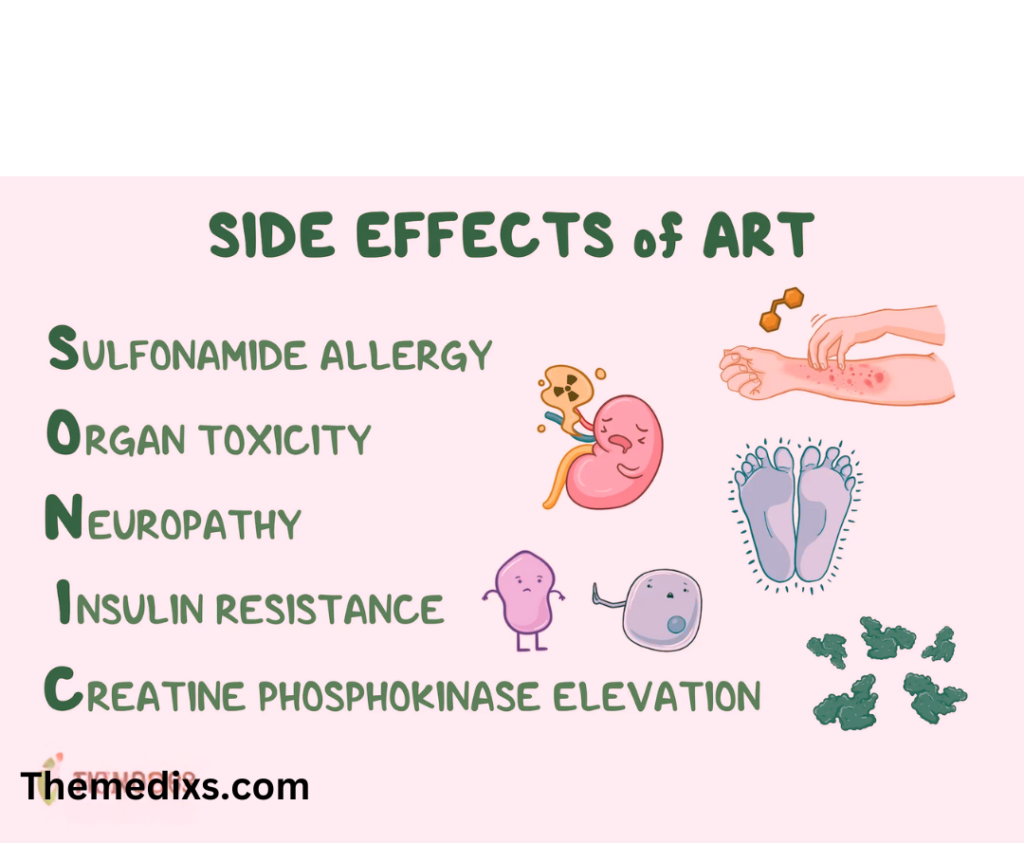

While modern ART regimens are safer and more tolerable than earlier treatments, side effects still exist. Common side effects include nausea, fatigue, diarrhea, and headache, though those often improve over time. Long-term use of ART can result in more severe issues, which includes liver toxicity, bone density loss, and cardiovascular disease. Regular medical check-ups are essential for managing those risks and adjusting treatment as needed.

Another challenge is drug resistance, which occurs when HIV mutates and becomes less responsive to specific ARVs. Resistance is more likely if a patient does not adhere to their treatment regimen, underscoring the significance of consistency in ART. To combat resistance, healthcare providers may switch patients to different pills or drug classes to maintain viral suppression.

6. Access to Antiretroviral Therapy and Global Initiatives

Access to ART has improved significantly in recent decades, thanks to global health initiatives and partnerships. Programs just like the President`s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and The Global Fund have provided financial help and resources to countries heavily impacted by HIV. Additionally, organizations which includes UNAIDS and WHO advocate for universal access to HIV treatment, prevention, and care.

Despite progress, disparities in ART access persist, particularly in low-earnings countries and marginalized communities. Barriers consist of high drug costs, constrained healthcare infrastructure, and social stigma. Efforts to address those challenges include generic drug production, community-based care models, and advocacy for human rights and health equity.

7. The Future of Antiretroviral Therapy: Innovations and Long-Acting Treatments

The future of ART is promising, with ongoing research focused on simplifying treatment and enhancing patient outcomes. One area of development is long-acting antiretroviral therapies, which can be administered monthly or even quarterly instead of daily. For instance, long-acting injectable formulations, such as cabotegravir and rilpivirine, offer convenience and may improve adherence for some patients.

Another area of research is the pursuit of an HIV cure. While a cure remains elusive, scientists are exploring strategies such as gene editing, therapeutic vaccines, and immune-based therapies. These approaches aim to eliminate HIV from the body or enhance the immune system’s ability to control the virus without ART.

8. Living with HIV: Beyond Medication

While ART plays a crucial role in managing HIV, a holistic approach to health is essential for individuals living with the virus. Physical, mental, and social well-being are all important aspects of HIV care. Regular exercise, a balanced diet, and mental health support can enhance the effectiveness of ART and improve overall quality of life.

Furthermore, reducing stigma and promoting HIV education are key components of supporting people with HIV. Public awareness campaigns, community support groups, and open conversations help dismantle misconceptions about HIV and empower individuals to seek treatment and lead fulfilling lives.

Conclusion

Antiretrovirals have transformed HIV treatment, providing hope and improved quality of life for millions of people worldwide. By suppressing viral replication, reducing transmission, and enabling individuals to achieve undetectable viral loads, ART has turned HIV from a terminal illness into a manageable chronic condition. However, challenges such as drug resistance, side effects, and disparities in access remain. Ongoing research, advocacy, and innovation hold the promise of further advancements in HIV care, with the ultimate goal of achieving a cure. Until then, antiretrovirals continue to be a cornerstone in the fight against HIV, enabling those affected to live healthy, fulfilling lives and work toward a future free of HIV.