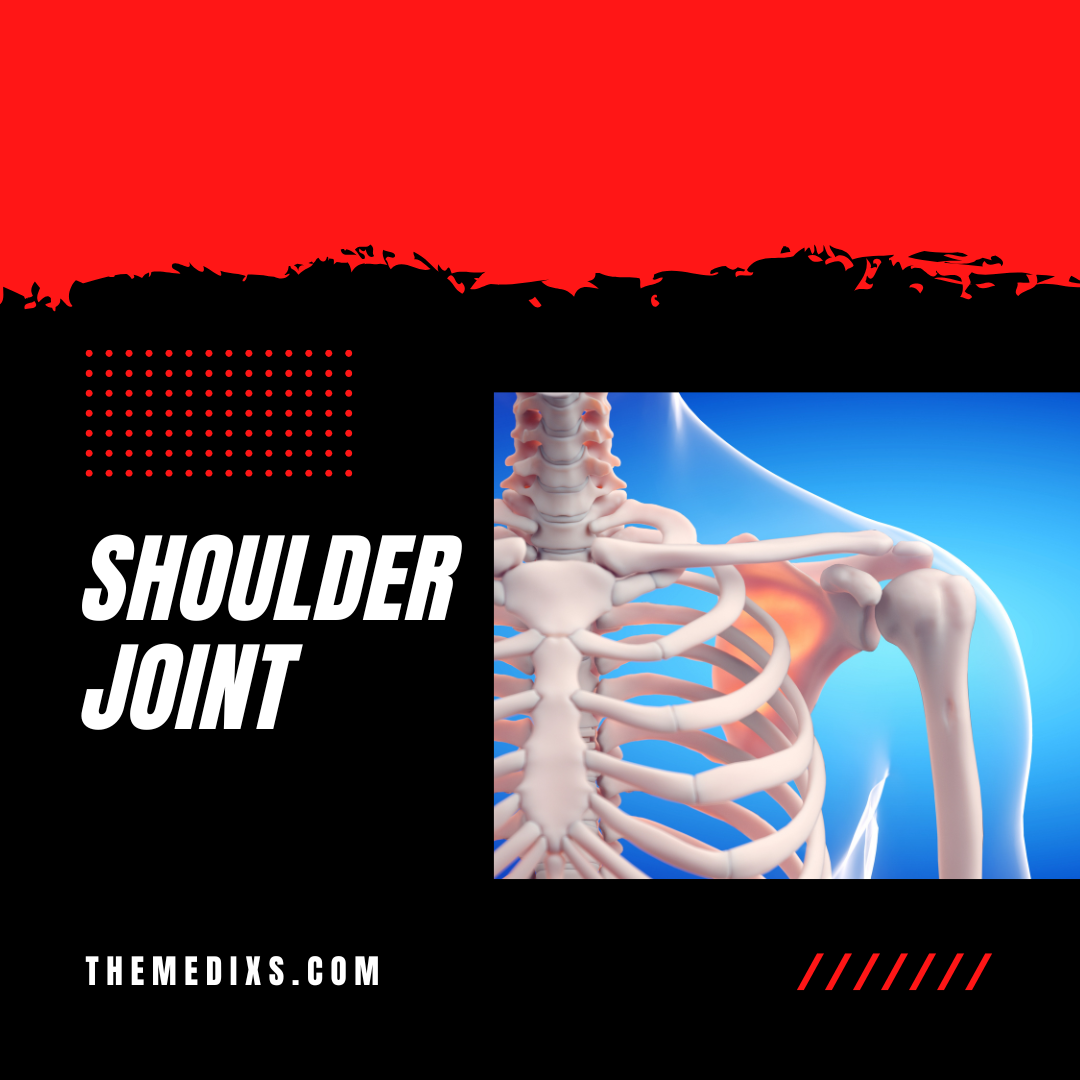

The shoulder joint is one of the most complex and mobile joints in the human body, essential for a wide range of daily activities. Its remarkable range of motion allows for actions like lifting, reaching, throwing, and carrying. However, this mobility comes at the cost of stability, making the shoulder prone to injuries and disorders. Understanding the anatomy, biomechanics, common conditions, and management options related to the shoulder joint is fundamental for healthcare providers, athletes, and anyone interested in maintaining joint health.

Anatomy of the Shoulder Joint

The shoulder is composed of three main bones:

- The Humerus (the upper arm bone)

- The Scapula (the shoulder blade)

- The Clavicle (the collarbone)

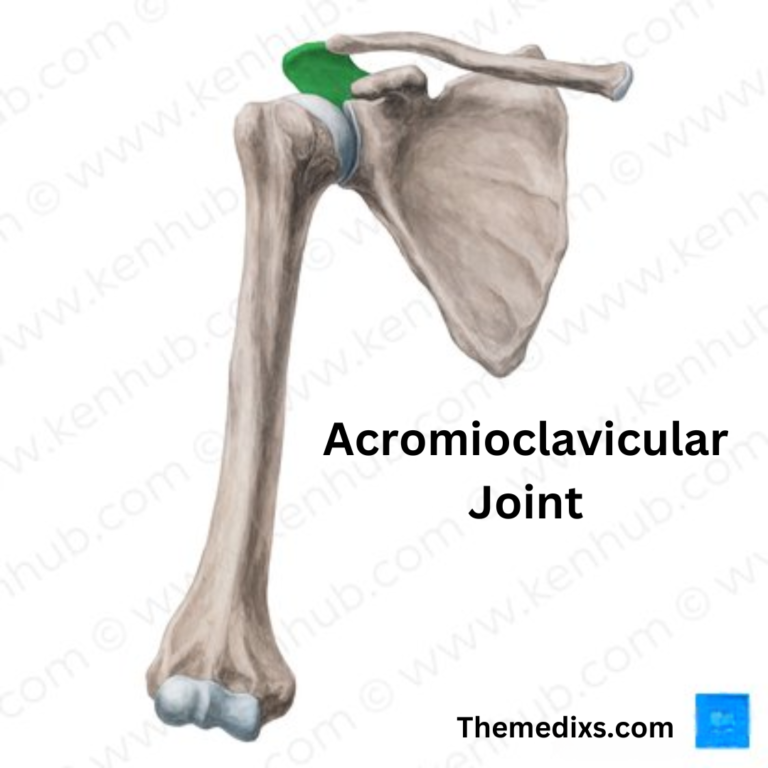

These bones come together to form two primary joints:

- Gleno-humeral Joint: This is the ball-and-socket joint where the head of the humerus fits into the shallow socket of the scapula, known as the glenoid. This joint allows for the shoulder’s extensive range of motion.

- Acromioclavicular (AC) Joint: This joint connects the scapula and the clavicle, helping stabilize the shoulder, particularly during overhead movements.

Supporting Structures

The shoulder`s stability is maintained by a network of muscles, ligaments, and tendons. Key structures include:

- Rotator Cuff: A group of 4 muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis) and their tendons that surround the gleno-humeral joint. They are essential for shoulder stability and rotation.

- Labrum: A ring of cartilage surrounding the glenoid, which deepens the socket and helps to stabilize the humeral head.

- Ligaments: These connect bones and provide passive stability, preventing excessive movement that could lead to dislocation.

- Bursae: Fluid-filled sacs located around the joint that reduce friction and cushion the bones, muscles, and tendons during movement.

Biomechanics of the Shoulder

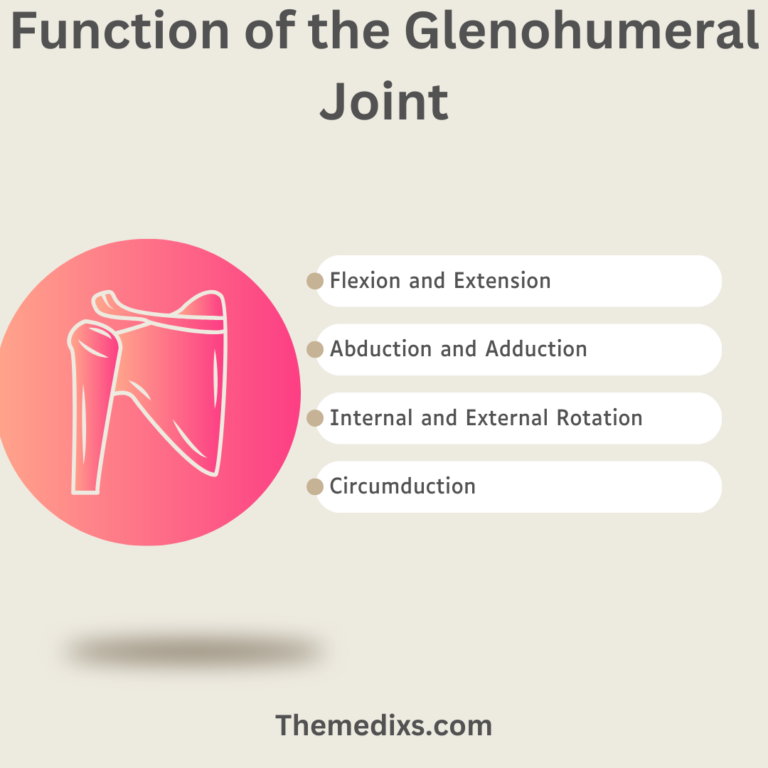

The shoulder joint allows for a greater range of motion than any other joint, which is divided into 4 primary movements:

- Flexion and Extension: Moving the arm forward and backward.

- Abduction and Adduction: Lifting the arm away from the body and bringing it back down.

- Internal and External Rotation: Rotating the arm inward and outward.

- Circumduction: A combination of the above movements, allowing the arm to move in a circular motion.

These moves are vital for activities which includes throwing, lifting, and pulling. The rotator cuff muscles play a vital role in guiding these motions by keeping the humeral head in the glenoid socket. This movement is often defined as the “concavity-compression mechanism,” where the rotator cuff compresses the humeral head into the glenoid fossa, allowing for controlled and coordinated movements.

Common Shoulder Conditions

Due to its mobility and complex structure, the shoulder joint is prone to a variety of conditions. Some of the most common consist of:

3.1 Rotator Cuff Injuries

Rotator cuff injuries are among the most frequent shoulder conditions. They range from slight inflammation (tendinitis) to severe tears. Causes may consist of repetitive stress, overuse, trauma, or degeneration over time. Symptoms typically include pain, weakness, and reduced range of movement, mainly during overhead activities.

3.2 Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

This condition takes place when the rotator cuff tendons become trapped and compressed between the humeral head and the acromion, leading to inflammation and pain. It is often seen in athletes and individuals who frequently perform overhead motions, like swimmers and painters.

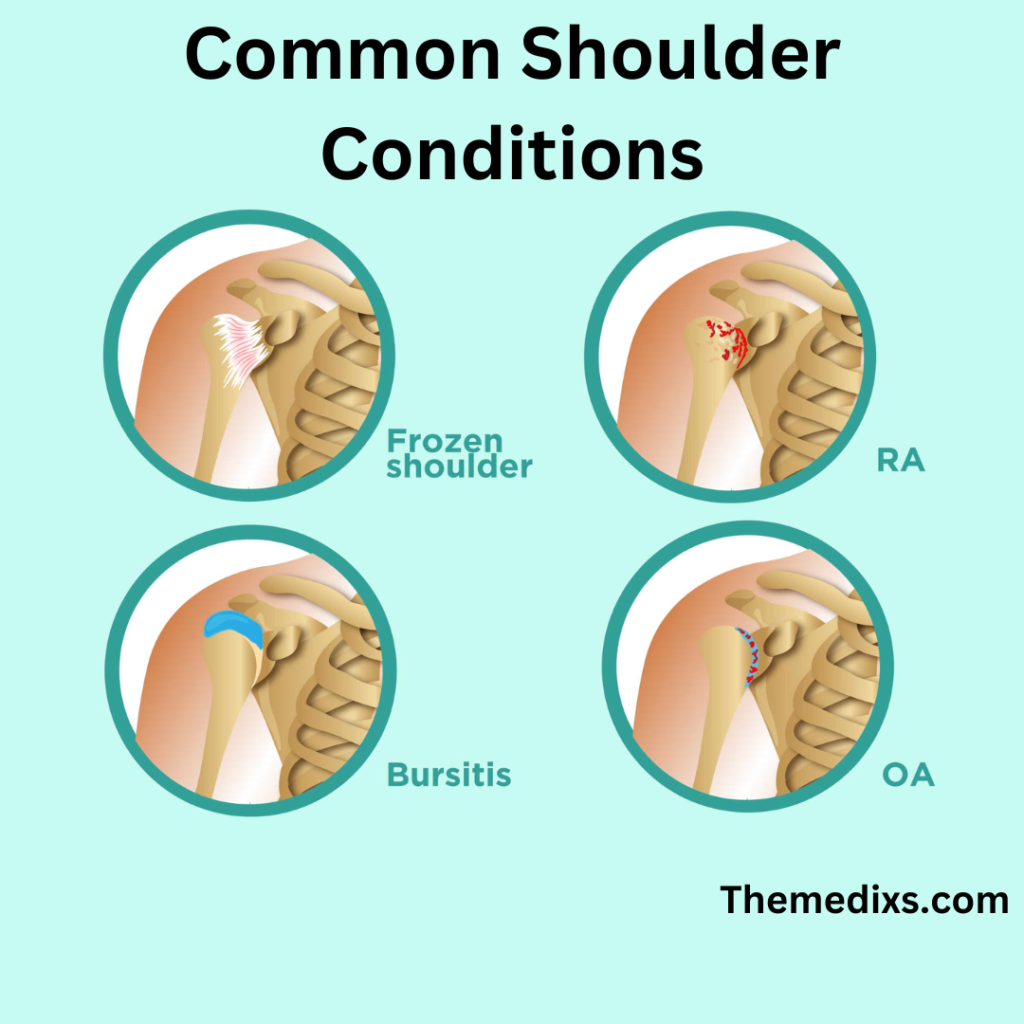

3.3 Frozen Shoulder (Adhesive Capsulitis)

Frozen shoulder is characterized by stiffness, pain, and limited range of movement in the shoulder. The condition progresses through 3 stages: freezing, frozen, and thawing. It is more common in people with diabetes and people who’ve gone through prolonged immobilization of the shoulder.

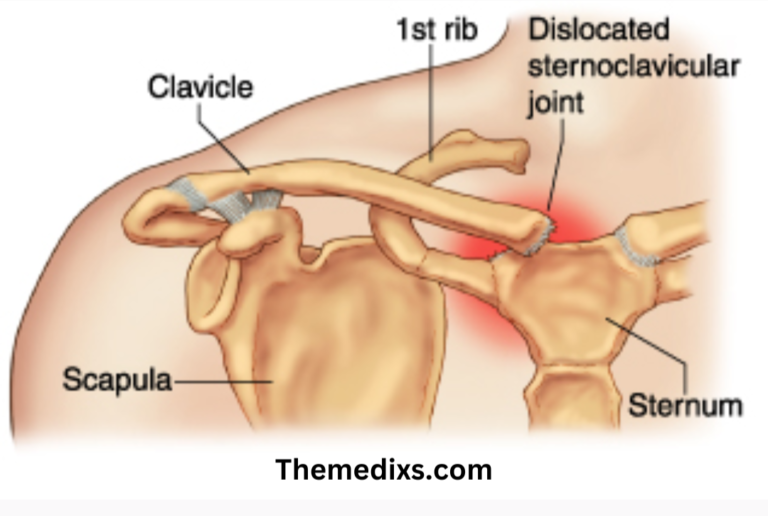

3.4 Shoulder Instability and Dislocations

Shoulder instability occurs when the head of the humerus slips out of the glenoid socket. This can occur because of trauma or repetitive stress at the shoulder, especially in sports that involve throwing or overhead motions. Dislocations are often related to ligament or labral tears, leading to recurrent instability if not properly managed.

3.5 Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder

Shoulder osteoarthritis involves the wearing down of the cartilage that cushions the bones, leading to pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility. This degenerative condition often affects older adults or individuals with a history of shoulder injury.

4. Diagnosing Shoulder Conditions

Diagnosis of shoulder conditions typically begins with a radical physical examination and a evaluation of clinical history. Key diagnostic equipment include:

- X-rays: Useful for identifying fractures, arthritis, or abnormal bone structures.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): Provides detailed images of soft tissues like muscles, tendons, and ligaments, making it beneficial for diagnosing rotator cuff tears or labral injuries.

- Ultrasound: Often used to evaluate soft tissue conditions, specially for real-time evaluation of tendon movement and integrity.

- CT Scan (Computed Tomography): Provides an in depth photo of the bones and is occasionally used for pre-surgical planning.

5. Management and Treatment Options

Treatment for shoulder conditions varies depending on the severity and type of injury. Some general treatment methods include:

5.1 Conservative Management

- Physical Therapy: Focuses on strengthening shoulder muscles, particularly the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers, to enhance stability and prevent re-injury. Physical therapy is often the first-line treatment for shoulder pain and dysfunction.

- Rest and Activity Modification: Avoiding activities that aggravate the condition allows the shoulder to heal. Modifying movements or adjusting activity levels is crucial, specially in repetitive stress injuries.

- Medications: Nonsteroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can help to manage pain and inflammation.

- Corticosteroid Injections: Corticosteroids are injected at once into the shoulder joint to lessen infection and offer pain relief. However, these injections are generally limited due to potential side effects from repeated use.

5.2 Surgical Intervention

In cases in which conservative management fails, surgical intervention may be necessary. Common tactics include:

- Arthroscopy: Minimally invasive surgery used to restore torn tissues just like the rotator cuff or labrum. It involves inserting a tiny camera and instruments into the shoulder joint thru small incisions.

- Open Surgery: In intense cases, open surgical operation can be required, specially for complicated rotator cuff repairs or shoulder replacements .

- Shoulder Replacement: In cases of advanced arthritis or irreparable damage, a shoulder replacement can be performed. This involves replacing the broken joint surfaces with artificial components to repair function and decrease pain.

Preventive Strategies for Shoulder Health

Maintaining shoulder health involves strategies to prevent overuse and injuries, particularly for athletes and individuals with physically demanding jobs. Key preventive tips include:

- Strengthening Exercises: Regularly perform exercises that target the rotator cuff, deltoid, and scapular muscles. Strengthening these muscles helps stabilize the shoulder joint, reducing the risk of injury.

- Flexibility Training: Maintaining flexibility in the shoulder and surrounding muscles, particularly the pectorals and latissimus dorsi, allows for a full range of motion and minimizes stress on the joint.

- Proper Technique: Athletes and manual laborers should be mindful of proper techniques to avoid excessive strain. For example, throwing techniques in baseball or weight-lifting forms are critical in preventing shoulder injuries.

- Gradual Progression: When increasing intensity in sports or exercises, progress gradually to avoid sudden stress on the shoulder joint.

Conclusion

The shoulder joint, while complex and vulnerable to injury, is essential for countless daily activities. Understanding its anatomy, biomechanics, and common conditions can aid in recognizing potential issues early and seeking proper management. For individuals experiencing shoulder pain or dysfunction, prompt medical evaluation and appropriate interventions can often lead to favorable outcomes. By incorporating preventive strategies, strengthening exercises, and flexibility training, it is possible to preserve shoulder health and maintain a high quality of life.

Shoulder health is a cornerstone of overall well-being and mobility, and taking proactive steps can go a long way in ensuring lasting function and comfort. Whether you’re an athlete, a fitness enthusiast, or simply looking to maintain mobility, caring for your shoulder joints will pay dividends over a lifetime.